Natural Capital’s future in UK policy after Brexit and the Protocol

by Inline Policy on 27 Jul 2016

Natural capital — a term for the earth’s natural resources and support systems that benefit human society — is the underlying focus of our environmental laws and policies. The Clean Air and (Clean) Water Acts of the US and UK are two aptly-named examples of previous policies designed to protect natural resources. At present, in Europe, the EU Circular Economy Package is a comprehensive set of measures and targets aimed at reducing our net consumption of raw materials (or ‘natural capital’). Likewise, climate change regulation and initiatives (e.g. the EU Emissions Trading System, EU Energy Efficiency Directive, EU Renewable Energy Directive) are focused on reducing our activities that deplete specific types of natural capital (specifically fossil fuels and rainforests, which sequester CO2 very effectively).

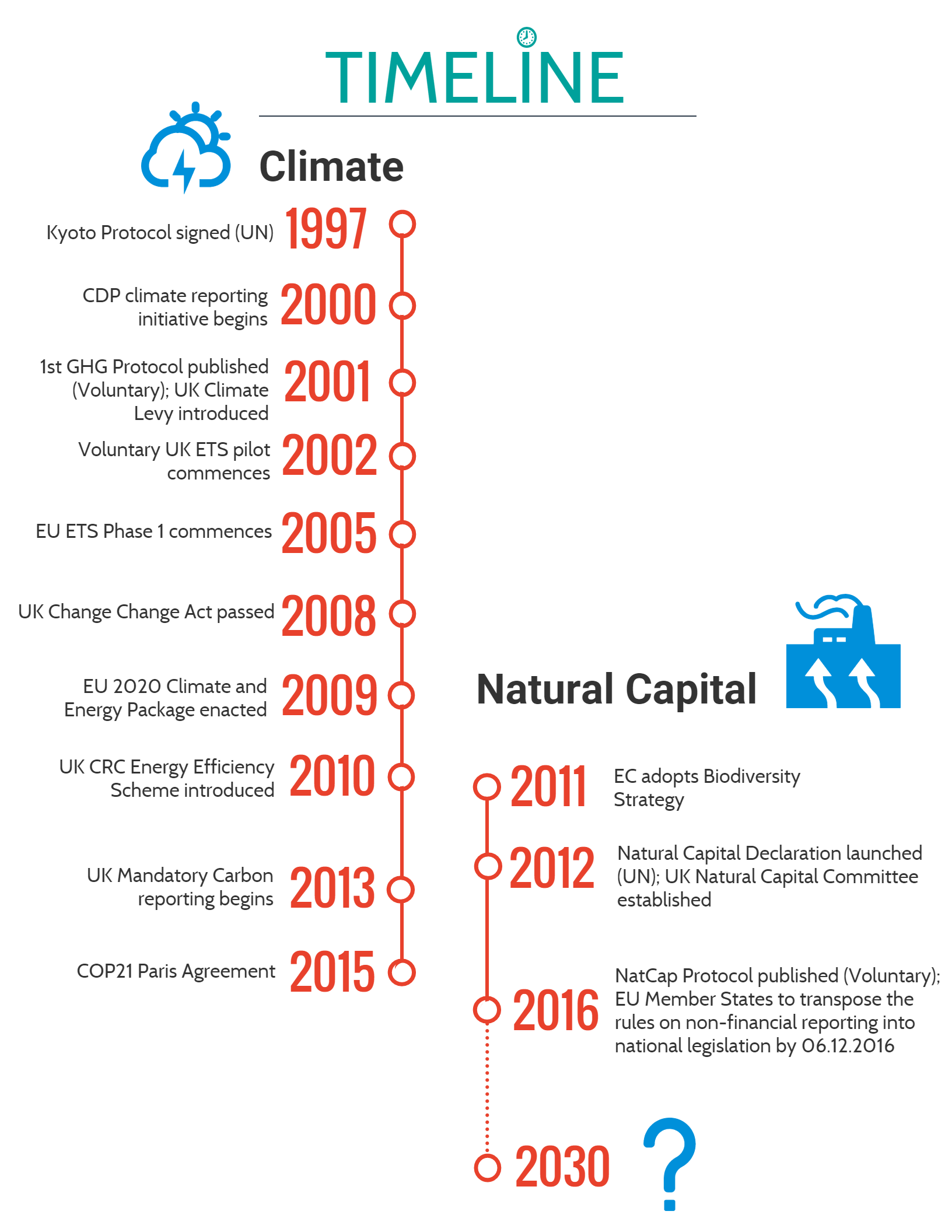

Beyond its implicit inclusion in single issue policies, natural capital is now a formal policy issue under consideration by governments, businesses, investors and NGOs. Natural capital policies and initiatives now exist across the UK, EU, and international levels. While still piecemeal at present, the integration of a natural capital ‘mindset’ into policy could yield a more holistic set of future environmental policies which are better suited for (1) understanding the environmental trade-offs of human activity and (2) informing strategic business and investment decisions. For corporates and investors, the climate change landscape changed dramatically between the launch of the Greenhouse Gas Protocol [i] in 2001 and the subsequent adoption of national and regional regulation in the lead-up to last year’s COP21 Paris Agreement. While natural capital assessment is a young discipline, both corporates and investors must be ready for a future where natural capital impacts and dependencies are assessed, reported, and possibly taxable.

This piece will recap: the launch of the Natural Capital Protocol; natural capital’s inclusion in current UK government policy; the impact of Brexit; and some potential directions that future natural capital policies could take.

THE PROTOCOL

On 13 July, the Natural Capital Protocol was launched by the Natural Capital Coalition (formerly TEEB for Business), marking a significant moment for the concept of natural capital. The framework offers a robust approach for organisations wanting to understand their use of, their impact on and their level of dependency on natural capital.

The 136-page guide is available to the public here, intended for use by businesses and investors as a process to support:

- Strategic planning and decision-making

- Supply chain risk-assessment

- Capital allocation

- Investment decision-making

- Operational decision-making

- External reporting

In addition to environmental management, a natural capital assessment can shed light on an organisation’s operational resilience, its impacts on local stakeholders, its exposure resource-related risks at a product or project-level, and the natural processes on which the business may depend (e.g. pollination of crops by local bee populations).

Further sector-specific guides are under development, with a current focus on the (1) Food & Beverage, (2) Apparel, (3) Real Estate, (4) Finance, and (5) Water sectors.

Key points from the Protocol

Purpose: At its core, the Protocol is a decision-making framework rather than a comprehensive reporting framework. This is reflected in the document, which focuses heavily on the natural capital assessment process but is less prescriptive on how to apply the results. Depending on the scope of the assessment, it could form the basis of external environmental reports or internal decision-making on projects and product design.

Organisational Scope: Compared to the established greenhouse gas accounting and reporting frameworks, the Natural Capital Protocol contains elements of both the Corporate Greenhouse Gas Standard and the Product Lifecycle & Project GHG Standards. In theory, the Protocol can be used for corporate, project, or product-level assessments. A corporate assessment would provide the most comprehensive picture and is most suitable for external reporting, but it would be complicated and time-consuming — especially if the organisation’s operations are widely spread across many geographies (impacting a wide range of natural capital & systems). A project or product-level assessment — typically undertaken to compare projects or products against each other or against a baseline — is easier to deliver as its geographic and temporal boundaries are typically much narrower and more focused.

Assessment Boundaries: As the Protocol encompasses all natural resources, assessments are potentially much broader in scope than those of traditional reporting standards (e.g. greenhouse gases only). As such, in addition to geographic and organisational boundaries, it is crucial to explicitly discuss and agree which natural capital impacts and dependencies are ‘material’ and to be included in the assessment.

Factors for Assessment: Natural capital assessments seek to determine (one or more of):

- Nature capital’s impact on an organisation - internalised financial costs of using natural capital (directly or through the value chain)

- How the organisation’s use of natural capital impacts society - impacts to wellbeing and social capital, the ‘social costs’

- The organisation’s dependence on natural capital - assessing the dependence on access to natural capital and the potential risks if these capital goods experience price volatility in future.

The inclusion of dependencies is a welcome addition. While topics of risk and dependence are sometimes reviewed for specific issues (e.g. climate change risks in the risk management section of the CDP reporting initiative), the Natural Capital Protocol offers a very direct, open approach to assessing an organisation’s reliance on the availability and affordability of specific natural resources.

Lastly, like many environmental accounting standards, the Natural Capital Protocol requires a high degree of interpretation when applied to specific organisations. That said, its comprehensive approach and detailed focus on the assessment process is a welcome signal that we may slowly be approaching the convergence and unification of the many and varied environmental reporting schemes and standards.

EXAMPLES OF CURRENT NATURAL CAPITAL POLICIES AND INITIATIVES

The Natural Capital Protocol - while valuable - did not launch into a policy vacuum. Both internationally and within the UK, the topic of natural capital has emerged across several different levels of government in recent years. This includes UK and EU legislation, as well as international initiatives supported by UK companies:

United Nations: In 2012, the UN’s Natural Capital Declaration was launched. An initiative for the finance sector (with UK signatory Standard Chartered), it aims to integrate natural capital criteria into financial products and services. In the context of the Protocol, NCD’s Working Group 3 is focused on Natural Capital Accounting and is collaborating with the Natural Capital Coalition to develop a Financial Sector Guidance to supplement the Natural Capital Protocol.

European Commission: The EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 established six targets for Member States on natural capital, specifically (1) species and habitats conservation, (2) ecosystems maintenance and restoration, (3) agricultural management to protect biodiversity, (4) sustainable fishing yields, (5) limiting invasive species, (6) contributing to global biodiversity protection efforts. That said, the resolution on the mid-term review in February expressed frustration on the slow progress of Member States in implementing many of the related environmental measures.

UK Government: The UK Government established an advisory committee— the Natural Capital Committee — in 2012 to provide recommendations on the management of natural resources. One core output is their annual State of Natural Capital report. The third report was released in 2015 and recommended investment in these areas of natural capital: (1) woodland planting, (2) peatland restoration, (3) wetland creation, (4) restoring fish stocks, (5) intertidal habitat creation. The Committee is currently in its second term, running from 2016–2020. As a relatively new committee, it will be instructive to monitor whether the UK Government (including this new Conservative administration under new leadership) accepts its future recommendations. In its response to the Committee’s third report, DEFRA [ii] was broadly supportive of some proposals like the creation of a 25-year plan and strategy, but less supportive of ambitious initiatives like the creation of “registers of natural capital”.

THE IMPACT OF BREXIT ON NATURAL CAPITAL-RELATED POLICY

While it is too early for the full implications to be known, the UK public’s vote to leave the European Union will invariably impact future UK environmental policy. The UK and the EU have a long and increasingly intertwined relationship on environmental policy. If the UK were to remain in the EEA, then it would stay subject to EU environmental laws. However, a non-EEA model could result in a more complex arrangement. EU policies with natural capital implications include the:

- EU’s Circular Economy Package: a primary aim of the concept of a circular economy is the conservation and restoration of ecosystems and natural capital. As it is unclear whether the UK will fully implement this legislation before the Brexit negotiations conclude, the UK Government could – in theory – choose a different path.

- EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Package: targeting the outcome of a stable global climate, this package is composed of major initiatives like Phase 4 of the EU Emissions Trading System and a 27% renewable energy target. If a non-EEA Brexit model is sought, the UK Government will need to clarify whether it seeks to align with the Commission’s climate and energy goals. That said, the recent acceptance of the UK’s Fifth Carbon Budget provides a strong signal of the UK’s domestic commitment to decarbonisation.

- EU Ambient Air Quality Directive: if a more formal ‘exit’ were to take place, it’s unclear whether air quality standards would be weakened. The UK has already implemented past air quality directives into UK law. Moreover, public opinion may swing towards wanting stronger air quality laws rather than weaker. The London Mayor’s Office announced that the equivalent of 10,000 Londoners die every year from conditions resulting from poor air quality, and that 86 London secondary schools experience NO2 levels above the legal limit.

FUTURE SCENARIOS OF NATURAL CAPITAL IN GOVERNMENT POLICY

The Natural Capital Coalition has described the Protocol as being “driven by the market rather than regulation”. And while this is laudable, it is unlikely that the future of nature capital will be purely voluntary initiatives. We expect that formal government policy will begin to fill the void just as it did for climate policy:

With a voluntary Protocol framework in place, the natural capital—climate change comparison seems apt. Investor pressure for more corporate transparency on natural capital risks seems likely. Investors already apply pressure using the CDP reporting initiative to gain corporate disclosure on risks posed by climate change, water scarcity, and use of forest commodities. As voluntary reporting becomes entrenched, it is increasingly likely that policymakers will propose a mandatory reporting scheme. And as with climate change emissions – once a standard reporting regime is in place – natural capital offers governments the same revenue-raising opportunity to regulate consumption through taxes or market-based instruments. Alternatively, if a business’s use of local natural capital is poorly managed and results in a severely negative outcome for local stakeholders (e.g. a spill that damages local land or water resources), natural capital policy may instead be created by a reactionary governmental response to a high-profile crisis.

While there are several potential paths for natural capital in future policy-making, we will outline three policies that already exist and could be expanded to include natural capital:

- Natural Capital embedded into a ‘Mandatory Natural Capital Reporting’ scheme

- Natural Capital incorporated into UK Planning Consent

- Natural Capital Budgets in the UK

Natural Capital embedded into a ‘Mandatory Natural Capital Reporting’ scheme

Currently: Voluntary organisations have spent years building social acceptance for annual corporate reporting of specific natural capital impacts. CDP operates a globally recognised, investor-led corporate disclosure initiative on natural capital use linked to the issues of climate change, water scarcity, and deforestation. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) has developed and evolved a comprehensive framework on sustainability reporting topics. In recent years, Government activity is catching up to voluntary initiatives. In 2013, the UK Government introduced Mandatory Carbon Reporting for listed companies. At EU level, rules on non-financial reporting are forthcoming:

Certain large undertakings should prepare a non-financial statement containing information relating to at least environmental matters, social and employee-related matters… should include a description of the policies, outcomes and risks related to those matters and should be included in the management report of the undertaking concerned. [iii]

Following a consultation in early 2016, the European Commission is now preparing non-binding guidelines for a reporting methodology of non-financial information due in December 2016.

In Future: As the current glut of reporting frameworks, voluntary reporting initiatives, and ad hoc client reports compound, a UK Government initiative consolidating these requirements could gain private sector support. Expansion of an existing reporting requirement like the UK’s Mandatory Carbon Reporting to include natural capital would be one route. There are some weak signals that Government also desires a more joined-up approach to environmental reporting. For example, the UK Government guidance on Mandatory Carbon Reporting compliance is only found in DEFRA’s full Environmental Reporting Guidelines document.

Natural Capital incorporated into UK Planning Consent

Currently: Planning consent in the UK is often conditional on the developer’s ability to mitigate the negative impacts of a new development through mechanisms like Section 106 agreements or the Community Infrastructure Levy. These agreements can place conditions or restrictions on the acceptable types of land use and on what processes/activities can take part on this development.

In Future: In a future with greater resource constraints or more ambitious regulators, local communities could use natural capital obligations as a mechanism to ensure that their local resource availability and quality are maintained alongside new development. An existing example of this type of measure is Birmingham’s addition of seven new planning principles to be used in assessing city development plans (Green Living Spaces Plan).

Natural Capital Budgets in the UK

Currently: The 2008 Climate Change Act instituted the process of creating five-year carbon budgets, i.e. a limit on the amount of CO2 the nation can emit each year. The recently released fifth carbon budget set targets for the 5-year period of 2028–2032. This process provides industry, investors, NGOs, and the public with long-term policy certainty on the ‘direction of travel’.

In Future: One extension of this success in implementing carbon budgets would be instituting natural capital budgets. The introduction of natural capital budgets — while complicated and certain to face resistance — could also offer a holistic approach to environmental policy that combines a series of policy issues into one package. While futuristic in some senses, aspects of this idea are already being floated. Returning to the Natural Capital Committee’s third report, the NCC recommended national accounts should include a “national balance sheet of the value of our natural assets” and that “organisations should create a register of natural capital for which they are responsible use this to maintain its quality and quantity” [iv].

The challenge with designing national environmental legislation – as with climate change – will be delivering the intended environmental protection without promoting environmental leakage (the movement of polluting activities to areas with less stringent regulation). To alleviate this, any efforts towards a national policy will require engagement and inclusion of the manufacturing sector.

IN CONCLUSION

While the term has existed for decades, natural capital does now seem to have truly arrived, finally achieving a degree of recognition and consideration in both corporate sustainability strategy and in government policy.

However, its future position in UK environmental policy (aside indirect inclusion in climate change and circular economy policy) is still fairly uncertain, complicated further by the recent Brexit decision.

A more fundamental question is whether investors or governments will lead the charge. As natural capital – like climate change – is a more complex environmental issue to consider, it is less likely that natural or manmade disasters will lead to creation of comprehensive natural capital policies (in the same way that extensive flood damage is not currently the driver of climate change mitigation policy). It is more likely that natural capital will follow the path of climate change policy, with investor pressure leading to an increased volume and quality of corporate reporting on natural capital topics. And as before, the UK government could convert this existing framework into a form of mandatory reporting (e.g. in company accounts).

On the local level, both government and investors could opt to play a stronger role. Whether through planning conditions, levies, or similar mechanisms, local governments can use natural capital policy as a method of environmental protection (and revenue-raising). Meanwhile, investors who provide project financing may begin to include natural capital assessments in their list of evaluation criteria. The assessment of natural capital dependencies offers a useful review of risks that could impact a project’s success.

The new Protocol provides an important framework that standardises natural capital assessment. In the coming months, it will become clearer whether it is investors, governments, or corporates who are taking the most pro-active approach.

[i] The GHG Protocol is the most widely used international greenhouse gas accounting tool for assessing, measuring, and reporting emissions. The first edition of The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Corporate Standard) was published in 2001. (http://www.ghgprotocol.org/about-ghgp)

[ii] The UK Government’s Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs. A ministerial department supported by 33 agencies and public bodies, DEFRA is responsible for several natural capital topics including aspects of natural environment conservation, agriculture, waterways, fisheries, and forestry. DEFRA also acts as the Secretariat for the UK’s Natural Capital Committee.

[iii] http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0095&from=EN

Title image credit: Unsplash.com

Topics: Energy policy, UK politics, Climate Change, Brexit

Comments