Robots and liability issues: the future regulatory framework

by Inline Policy on 30 Jun 2016

Robots are rapidly gaining public visibility as their development accelerates in conjunction with recent innovations in the domains of artificial intelligence, machine learning, machine-to-machine and machine-to-human interaction.

The annual increase in the uptake of industrial and service robots is rapidly becoming a subject of political debate both in national and European fora. There is currently no specific legislation in place regulating the design, the applications, the use and the characteristics of robots.

The European Parliament has recently begun debating a proposal that calls on the European Commission to take the initiative and propose the introduction of a regulatory framework in the field of robotics.

A clear definition

The debate at academic, industrial and political levels acknowledges that, in order to propose a regulatory framework for robots, it is first necessary to agree on what the term “robot” means. This includes, providing a definition which then constitutes the basis for identifying the ethical and legal issues that will be at the core of the political debate.

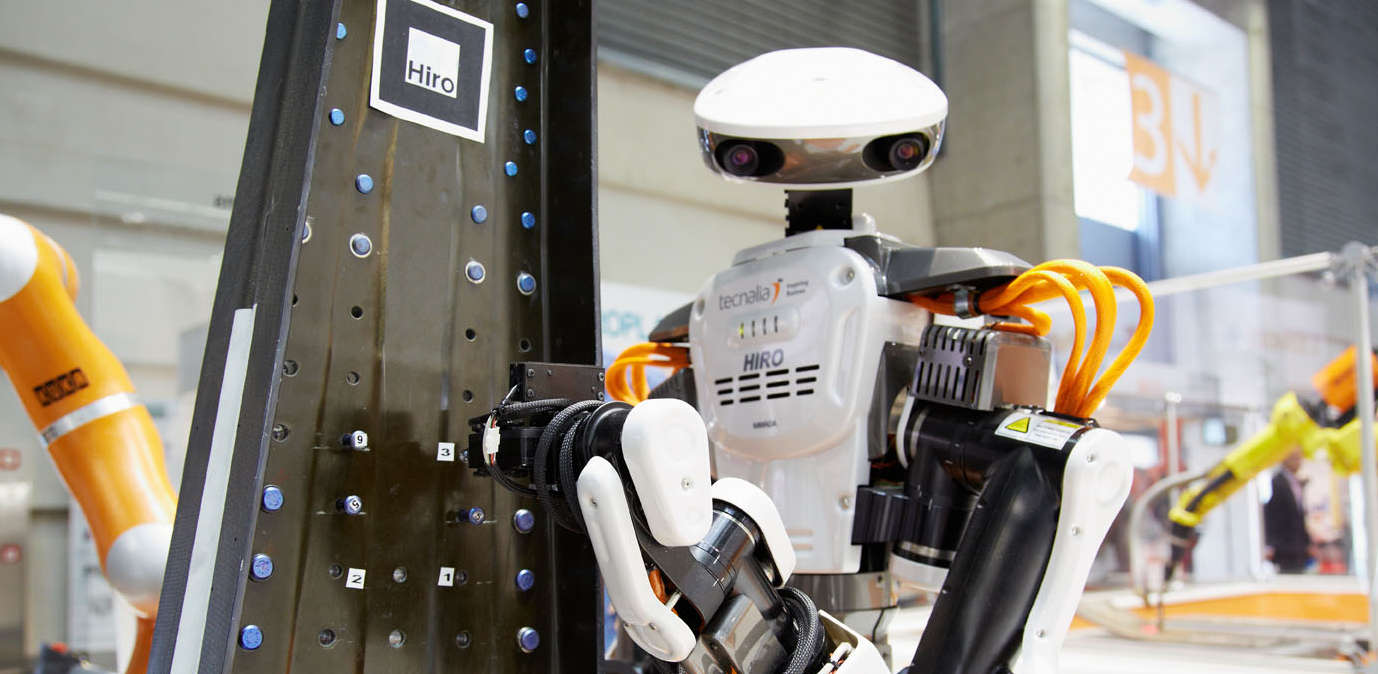

Indeed, the term “robot” can mean different things to different stakeholders. Specifically, virtual robots, softbots, nanorobots, biorobots, bionics, androids, humanoids, cyborgs, drones and exoskeletons are just some of the terms currently used to designate a robot, or some aspects of robotics, in scientific and popular languages.

Let us take a step back and see what the basis for the current political debate is.

A draft report recently published by the European Parliament calls on the Commission to propose a common European definition of smart autonomous robots and their subcategories by taking into consideration the following characteristics: it should acquire autonomy through the use of sensors and/or by exchanging data with its environment (inter-connectivity); it trades and analyses data; it has a physical support, a body, of any shape; it adapts its behaviours and actions to its environment; and finally it is capable of self-learning, though this last criteria is indicated as optional.

It is then possible to classify robots based on some characteristics and features:[1]

- Use or task, meaning the specific function the robot is designed to perform. Conventionally, applications are divided into two macro categories: service and industrial applications. A service robot operates in semi or complete autonomy in order to perform services for the benefit and well-being of humans and equipment, excluding any manufacturing operations. An industrial robot is defined by the International Organisation for Standardisation as an automatically controlled, reprogrammable, multipurpose manipulator programmable in three or more axes.

- The environment, or the space where the robot carries out its activity. There are robots that perform actions in a physical environment, such as space, air, land, water, the human body (or other biological environments). However, some other robots operate in non-physical environments, known as bots. These are gaining great popularity since their uptake by several large online platforms, including Facebook, Google and Microsoft.

- The body, as robots can be distinguished by whether they are embodied or disembodied.

- Machine to human interaction. This category takes into account the relationship between robots and human beings and it includes modes of interaction, interfaces, roles, and proximity between humans and robots.

- The degree of autonomy, which specifies how independent the robot is from an outside human supervisor in the execution of its task in its environment.

A clear definition of what is considered to be a robot is the first step that regulators need to undertake in the process of designing a regulatory framework. This is because the benefits stemming from the uptake of robots are nuanced by a set of risks, generated by the features mentioned above, related to human safety, privacy, integrity, human dignity, autonomy, data ownership and liability.

Liability related issues

In 1942, Isaac Asimov, an American author of sci-fi novels and a professor of Biochemistry, was the first to try to devise a set of rules applicable to robots in a hypothetical future.[2]

Although these laws are derived from fictional narrative, they are regarded by many as the most coherent attempt so far to establish a framework of laws in which smart independent robots can operate. These laws state that:

1) a robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm;

2) a robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law;

3) a robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Another law, added later by Asimov, states that ‘a robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm’.

The European Parliament has said that Asimov’s Laws can be taken as the starting point for the current debate about a regulatory framework for robotics. This is because, until the moment when robots become or are made self-aware and an appropriate legislative framework is in place, Asimov's Laws must be regarded as being directed at the designers, producers and operators of robots, since those laws cannot be converted into machine code.

Liability is the core issue in the political debate: who is ultimately responsible for actions, carried out by a robot, that cause damage to a person, equipment, goods, or animals? It is necessary for policy makers to devise a framework for, first of all, identifying the ultimately responsible parties and then measuring their liability. One proposed option is to establish a framework for liability levels that is proportionate to the level of instruction given to the robot, and of its autonomy. This would translate into a system in which the greater a robot's learning capability or autonomy is, the lower other parties’ responsibility should be, and the longer a robot's “education” has lasted, the greater the responsibility of its “teacher” would be.

The more autonomous a robot is, the less it can be considered a simple tool in the hands of other actors (such as the manufacturer, the owner, the user, etc.). For this reason, the current ordinary rules on liability are insufficient to deal with the emergence of robots. Mady Delvaux MEP, rapporteur for the EP Draft report on civil law rules for robotics, has called for new rules which focus on how a machine can be held – partly or entirely – responsible for its acts or omissions. As a consequence, it becomes more and more urgent to address the fundamental question of whether robots should possess a legal status: robots' autonomy raises the question of their nature in the light of existing legal categories – of whether they should be regarded as natural persons, legal persons or objects – or whether a new category should be created, with its own specific features and implications as regards the attribution of rights and duties, including liability for damage.

The problem is that, under the current legal framework, robots cannot be held liable per se for acts or omissions that cause damage to third parties. The existing rules on liability cover cases where the cause of the robot’s act or omission can be traced back to a specific human agent such as the manufacturer, the owner or the user, and where that agent could have foreseen and avoided the robot’s harmful behaviour.

The draft report also proposes that a possible solution to the complexity of allocating responsibility for damage caused by increasingly autonomous robots could be a mandatory insurance scheme. However, unlike the insurance system for road traffic, where the insurance covers human acts and technical failures, an insurance system for robotics could be based on the manufacturer’s perceived responsibility for the autonomous robots it produces.

Furthermore, the draft report proposes that the future legislative instrument should provide for the application of strict liability as a rule, thus requiring only proof that damage has occurred and the establishment of a causal link between the harmful behaviour of the robot and the damage suffered by the injured party.

What next

It is of vital strategic importance for the manufacturing sector as a whole, not just robot designers and producers, to follow these new regulatory developments very closely and engage with key decision-makers at European and national levels well.

For robots manufacturers, the risk otherwise is that they will find themselves forced to comply with rules that could impact their future without having a strategy in place to manage change.

For the wider manufacturing sector, the risk is that the uptake of robots and the innovations that it can trigger might be hampered by a legislative framework not adequately tailored to the priorities of businesses. The potential of this technology is huge, and both innovators and regulators will need to engage in discussions to reap the benefits of the robotics era, whilst minimising the risks.

Topics: European Politics, Autonomous vehicles, UK business, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Tech

Comments